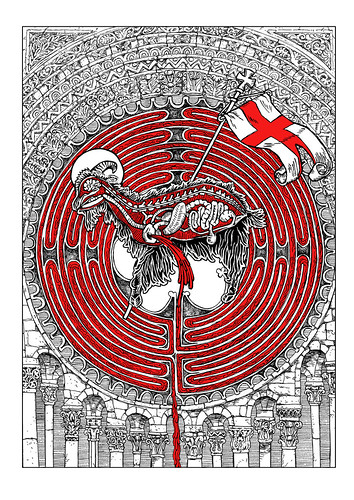

The version of Paradise that Tintoretto painted for the Ducal Palace in Venice in 1592 is reproduced above. It is referred to several times in the text of Five Wounds (although I never name the artist in the novel). It is also quoted visually in a diptych on pages 28-29. In the standard scholarly biography of Tintoretto, by Eric Newton, there is a long passage on the painting, which I sent to Dan as reference material. Starting on p. 198, this passage reads as follows.

The finished painting is, as it were, a colossal three-dimensional wall-paper, a vast pattern representing space itself, marked out in dark patches, between which one’s eye [199] seems to penetrate into a radiant, crowded infinity, as though innumerable groups and clusters of figures had arranged themselves like galactic systems one behind the other in the interstellar void.

At first glance this absence of formalized planes and, in particular, the lack of a base with a firmly established foreground, confuse and bewilder the eye, but gradually the brave pattern, with the noble silhouettes of Christ and the Virgin as its climax, asserts itself. One begins to see it as the only possible solution to the problem. .... The finished painting is ... governed by none of the normal optical laws. The effect is not of standing in this world and gazing into the remote distances of the next but of seeing through a glass wall into a celestial aquarium in which both light and distance mean nothing. Single figures and groups of figures float through this supernatural ether, towards or away from the glass wall, in a ceaseless rhythmic movement, not under the spell of gravity but in obedience to the magnetism that radiates from Christ and the Virgin who bend gently towards each other above them. The gaps between them are not areas of radiance but glimpses of interstellar space, and that space is not so much occupied by the myriads of the blessed as composed of them. The radiance in which they have their being has become interchangeable with their being itself. The world of visual experience with its vocabulary of ‘near,’ ‘far,’ ‘upper,’ ‘lower,’ ‘towards,’ ‘away from,’ no longer exists. This, in purely practical terms, gives Tintoretto the immense advantage of being able to enlarge or diminish any figure at will without contradicting the laws of perspective; it retains the medieval system of scale by importance without abandoning the Renaissance system of scale by distance.

Newton’s insistence on seeing the Paradise as the crowning achievement of Tintoretto’s career (he died in 1594) seems misguided, given that the painting is now usually attributed jointly to Tintoretto’s son Domenico, a much inferior artist, and to the workshop. With this revised attribution in mind, the peculiar composition seems less the result of unconventional artistic genius and more like incompetence, but this illustrates a more general point about the nature of interpretation, which is always the result of a series of enabling preconceptions. As Gabriella concludes in Five Wounds, an illegible message was easier to transcribe if one already had some idea of what it might say.

Newton starts with the presumption that the painting is by Tintoretto, and Newton knows that Tintoretto is a genius. Everything in his account follows from that basic premise. My own, admittedly uninformed, first impression was that it was rather turgid, whoever painted it, but that makes Newton's achivement in this passage even more impressive. It is a brilliant piece of creative writing, insofar as it succeeds in reinscribing this apparently mediocre work as a masterpiece. Even so, Newton's approach seems rather old-fashioned now (the biography was published in 1952), and not only because it is based on obsolete research.

Newton is a late descendant of a tradition of conoisseurship that goes back to Giorgio Vasari, who founded art criticism as an academic discipline in the sixteenth century, and in the process suggested what it is that critics should be doing. Vasari’s purpose was three-fold: to provide clear descriptions of paintings that, in an age before photographic reproduction, could often only be viewed in situ; to establish a set of criteria by which one could distinguish great painting from good, and good from bad; and to establish a canon of painters who, collectively, embodied those criteria.

Vasari was perhaps the first major theorist of Western art, but one of the first important art critics in the same tradition was Pietro Aretino, whose literary output was far more varied and whose ideas on art were far less systematic, but whose letters and sonnets about Titian helped to establish the latter as one of the most successful painters in Europe in the middle of the sixteenth century. For example, Aretino described Titian’s portrait of Eleonora Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino (above), painted c. 1536-8, as follows.

The union of colours laid in by Titian’s brush expresses, besides the concord that reigns in Eleonora, her gentle spirit. Modesty [modestia] is seated with her in an attitude of humility, purity resides in her dress, consciousness of her virtue [vergogna] veils and honours her breast and hair. Love fixes on her his lordly glance. Chastity and beauty, eternal enemies, are in her likeness and between her eyelashes the throne of the Graces is seen.

The flattery is obviously aimed at Eleonora as well as Titian, but its effect depends on the assumption that Titian’s painting displays her character rather than merely representing her appearance. According to Aretino, the painting opens a window into Eleonora's soul. Eleonora, the painting, Aretino's description: each of these things is, in some sense, identical with the others. There is no mediation. Everything is transparent.

Aretino claims to be ‘reading’ the portrait, but what he’s actually doing is interpreting it, and, as with Newton's description of the Paradise, reinscribing it: that is, writing meaning over it. I defy anyone to look at this picture unprepared and say, ‘I see the concord that reigns in Eleonora, her modesty, purity, etc., etc’. Aretino is trying to influence the way we read the portrait by annotating it, but at the same time insisting that his annotations add nothing that is not already there.

One way of clarifying this problem is to reverse the terms of the relation between word and image. Would someone who only had Aretino’s description of Titian’s portrait – or Newton’s description of Tintoretto’s Paradise – be able to visualise the paintings in question accurately on the basis of the description alone? The answer is surely, ‘No’.

I am interested in this question for practical reasons, because my collaboration with Dan involved writing descriptions of pictures that did not yet exist, which Dan then used to bring these potential pictures into actuality. In this case, the description generated the picture, rather than the other way round, but that actually makes the role of interpretation more explicit. Dan’s illustrations were always a loose translation of my instructions, inevitably, because they were rendered in a different medium by a different process and via a different sensibility. They always added something to the written description, no matter how exhaustive my instructions aspired to be. So I could never predict what they would look like.

One might argue that Dan was doing the same thing that Newton and Aretino were, but in reverse. I think it's a bit more complicated than that. We may see Tintoretto's and Titian's paintings in a new light as a result of their efforts, but Newton and Aretino are not actually attempting to open a conversation: rather, they aim to have the last word. The painter, or rather the painting, has no right of reply. In the classic version of connoisseurship, the definitive interpretive act is an attribution: 'Yes, this painting is an authentic Tintoretto'. But the authority of that attribution derives not from Tintoretto himself, who lacks the insight to understand his own talent (Tintoretto does not know what it is that makes him Tintoretto), but from the disinterested mind of the connoisseur.

What I was doing, by contrast, was inviting Dan to alter the meaning of my work, to divide the responsibilities of authorship with me (quite literally in the case of Five Wounds).