I have nearly

finished a new novel, Brethren. I am now thinking

about possible illustrations for this novel. As usual, I am collaborating with

Dan Hallett to create a few samples for publishers, who can then decide if this

is something they would like to see more of. The picture above is the first

such sample. The rest of this post is a simplified account of the creation of

this illustration, including: some general notes I wrote for Dan to introduce

the novel; a short extract from chapter 15; and a script for this particular

illustration.

General Notes for Dan

Brethren is set

in evangelical Protestant church (the Brethren are a particularly austere

non-conformist group). So my original idea was that its depiction of angels and

demons would be rigorously Protestant, and use only Biblical sources. This is

important because most of our ideas about demons, and some of those about

angels, actually come from the New Testament Apocrypha (i.e. works judged

unreliable by the early church) or the similar Old Testament Pseudepigrapha.

But Robert’s theories about angels are taken solely from the canonical books of

the Bible, which leads him to rather different conclusions to those of

Christian traditions informed by these other sources.

However,

Brethren is

also a horror story: that is, a story in the Gothic tradition, in which the

protagonist is haunted by repressed secrets. And one of the ideas behind the

Gothic as it emerged in eighteenth-century novels is that England is similarly

haunted by its medieval past: that is, by its Catholic past. The ruined

monasteries and abbeys and castles that were the settings for Gothic fiction

were ruined because of the destruction caused by Henry VIII’s reformation.

So

my protagonist tries to construct an austere Protestant system of belief, but

he’s haunted by Catholic ideas, which seep into his visions and experiences:

e.g. transubstantiation (the idea that the bread and wine somehow become the

actual body of Christ during communion), and the Harrowing of Hell (the idea,

derived from the so-called Gospel of Nicodemus, that Christ preached to the

imprisoned spirits in hell between his death and resurrection). I also draw on

late-medieval Catholic sources like morality plays, in which the soul of

Everyman was besieged by demons and angels; and medieval characters like Joan

of Arc (who was visited by saints and angels).

So

I want the images to have a late-medieval, Catholic feel, with a visual style

from the 15th and early 16th centuries (i.e. just before the Reformation), but

(if and when they include human figures) these will be dressed in 1980s clothes

(I have some photos I can supply for reference, but they’re not necessary for

this particular illustration). I was thinking of an engraving style, but

really, if we’re talking 15th century, woodcut is more appropriate (and will

probably be easier to do).

The

sample illustration is based on the idea of the scapegoat from Leviticus in the

Old Testament, which is discussed in chapter 15 of the novel. The relevant

extract is appended below. Robert, the main protagonist, is the only one who

can see or hear the ‘girl’, a.k.a. the demon Azazel. His friend Tracey’s there

for moral support, as is Jenny, who’s an R.E. teacher with a background in

theology. Mark’s an autodidact lay preacher. He’s the one actually performing

the exorcism.

Novel Extract

‘My name is

Azazel,’ the girl says.

Robert

copies her. ‘Az-a-zel.’

‘What

does that mean?’ Mark says. ‘Who are you?’

‘Ask

Jenny,’ the girl says. ‘She knows.’

‘Jenny

knows what it means.’

‘Me?

I’m not …’ Everyone looks at her. ‘Fine. It’s from Leviticus. The ritual for

the Day of Atonement. It might not even be a name.’

‘It’s

my name,’ the girl says.

‘We

don’t have theological discussions with demons,’ Mark says. ‘They’ve got

nothing to teach us about God.’

Jenny

pulls her bag out from under the chair, and gets her Bible out. She places it

on her lap. ‘Maybe it’s something Robert needs to tell us.’

Mark

says, ‘Well, there’s no harm in reading from God’s Word. But I’m not having a

demon explain it to me.’

‘Take

your time,’ the girl says. ‘Talk it over.’

‘On

the Day of Atonement,’ Jenny says, ‘the High Priest stood before the Ark, in

the presence of God. But first he had to make a special sacrifice.’

‘Nothing

to do with demons,’ Mark says.

‘So

he took two goats, and he cast lots between them.’

‘That’s

you and Tracey,’ the girl says to Robert.

‘One

goat for God; the other … for Azazel.’

‘It

doesn’t say that.’ Mark gives in and goes to get his Bible from the top of the

dresser on the other side of the room. He gives the bed a wide berth.

‘You

won’t find it in the NIV,’ Jenny says. ‘Or the King James. Or the Living Bible.

They all translate it. But they’re guessing, because no-one knows what it

means.’

‘I

do,’ the girl says.

Jenny

says, ‘In Hebrew, it’s something like “taken away”; “removed”.’

‘Exorcised,’

the girl says.

‘In

the Greek version of the Old Testament, it’s “a thing that keeps illness away”.

Like a charm.’

‘Except

not like a charm at all,’ Mark says. ‘Because that would be the occult.’

‘In

the Latin Bible, it’s caper emissarius. Messenger goat. Scout, spy.’

‘Angel,’

Robert says.

Jenny

flicks through her Bible to Leviticus. ‘In English, it’s usually scapegoat, but

Tyndale invented that word in 1530 for his translation, and everyone else

copied him. Except the RSV.’ She reads, ‘The

goat on which the lot fell for Azazel shall be presented alive before the Lord

to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away into the wilderness to

Azazel.

‘So

the High Priest sacrifices one goat; sprinkles its blood in the Holy of Holies.

Then he puts his hands on the head of the other, and confesses the sins of the

people.’ She reads again. ‘The goat shall

bear all their iniquities upon him to a solitary land. To Azazel. Which

could just be a place in the desert. Or a demon who lives there.’

‘Both,’

the girl says.

‘Jesus,’

Mark says. ‘He’s the scapegoat.’

‘But

they don’t kill the scapegoat,’ Tracey says. She hooks her feet around the

front legs of her chair and looks down again.

‘Right,’

Jenny says. ‘Literally, “the goat who escapes”. Because it doesn’t matter what

happens to it, after they send it away.’

‘One

for God,’ the girl says, ‘one for me. But the one for God dies; and the one for

me lives.’

Robert

doesn’t believe her. ‘Maybe Azazel kills the scapegoat.’

‘Jesus

is the scapegoat,’ Mark says. ‘And He wasn’t sacrificed to a demon.’

Jenny

closes her Bible, but keeps her finger inside it to mark her place. ‘Why

Azazel, Robert?’ she says, as if he chose the name. ‘Did you hear it in a

sermon?’

Robert

makes his hands into fists. ‘No.’

‘In

the desert, outside the camp.’ Jenny taps her Bible against her knee. ‘The

Greek word for hell is Gehenna. Name of

a place outside Jerusalem where people sacrificed their children.’

‘Maybe

Abraham went there to kill Isaac,’ the girl says, drawing patterns on the quilt

with her finger.

‘In

Jesus’ day, it was abandoned, cursed. A rubbish dump.’

‘So

Azazel is hell?’ Robert says, thinking of Jesus in the wilderness, tempted by

Satan. Maybe that was Gehenna too.

‘I

don’t know.’

‘If

Azazel eats the goat, does that mean it’s eating sin?’

‘What

else would a demon eat?’ Mark says.

Jenny

says, ‘In medieval paintings, the entrance to hell is a mouth. So when Jesus

dies, it tries to eat Him. But He’s too pure; it can’t digest Him. So it spits

Him out.’

‘Does

Azazel spit the scapegoat out?’ Robert asks.

The

girl burps.

‘We

don’t need to know this,’ Mark says. ‘It’s not relevant.’

Jenny

says, ‘Christ bears the sins of the world, but He’s still pure. He takes the

penalty, but not the guilt.’

The

girl burps again, and says, ‘His flavour doesn’t change. He still tastes the

same.’

‘For

the scapegoat, it’s more like the other way round. It takes the guilt, but not

the penalty.’

‘You

take the penalty; Tracey takes the guilt,’ the girl says to Robert. ‘Or the

other way round. It’s up to you.’

‘I

don’t want it to be up to me.’

‘Robert,’

Mark says, ‘stop talking to it.’

‘But

it is up to you,’ the girl says. ‘So who do you want to be? The goat for God;

or the goat for Azazel?’

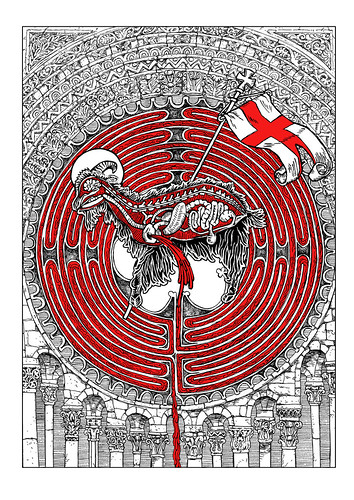

Script for Dan

A really boring

illustration of these ideas would be a picture of two goats: maybe one black,

and one white. So I thought, what if it’s not two goats? What if it’s half a

goat? This ties in to another famous Biblical story about King Solomon, who

decided to cut a baby in half to find out which of two women was the mother:

she was the one willing to give the baby away rather than see it harmed. In the

context of the novel, depicting the goat cut in half could suggest that choice

is painful, disruptive, and reveals secrets (the inside of the goat). It always

involves violence and the renunciation of possibilities (by choosing one thing,

by definition you exclude another).

I

started off by thinking of Damien Hirst’s Mother

and Child, but if you look at the cross-sectioned cow in that, its

interior just seems a mess. It’s difficult to make out the shapes of internal

organs, etc. So we want a goat cut in half, but rendered somewhat

non-realistically, more like the ‘self-dissecting man’ from the anatomy

treatises of Vesalius, who displays all his internal organs, etc. In fact, the

high priest often had to separate individual organs as part of the different

Old Testament sacrificial rites.

So:

a cross-sectioned black goat, with a (probably simplified and stylised) set of

visible internal organs.

The

idea that the scapegoat is Christ also made me think of the image of the Agnus

Dei, the Lamb who takes away the sin of the world, which is shown with a halo,

carrying a flag with a Saint George’s Cross. So our goat will similarly have a

halo and flag. It’s both the Lamb of God and the scapegoat. But a goat

(particularly a black goat) is normally a Satanic symbol, so it’s also both

Christ and the devil.

The

Hirst cows look very odd with only two legs, and similarly I suspect it will be

difficult to render a convincing two-legged goat. This is something you’ll have

to figure out. I guess the Hirst one is neither sitting nor standing, but

suspended, and that’s probably the impression we want too.

Brethren

also has several allusions to the Minotaur and the labyrinth, which represent

the devil and hell in medieval allegory, with Theseus as Christ, penetrating

the labyrinth to kill the devil. So one final layer is to have a red maze in

the background behind the goat. This maze begins / comes out / is analogous

with the spaces between the goat’s various internal organs, i.e. the organs sit

on a red background inside the goat, where they block out most of that

background, reducing the visible part of the background to a series of lines,

whose shapes resemble those of a maze / labyrinth. A drop / line of blood

trickles out of the goat and down onto the background of the page, where it

begins another, similar path through a larger maze / labyrinth. (N. B. For

reference, there’s a labyrinth filled by an advancing rivulet of blood in the

first Hellboy

film.)

The

blood coming out of the goat is therefore a trickling red thread like the

thread Ariadne gives to Theseus in the minotaur's labyrinth. So there's a sense

in which we should be able to see the blood flow as reversible: we should be

able to follow its thread from the outside inwards, as well as from the centre

out.

Mazes

/ labyrinths are common elements in the floor decorations of medieval

cathedrals, where they represent the idea of pilgrimage. Here’s the one from

Chartres: http://www.luc.edu/medieval/labyrinths/chartres.shtml

In this context, it's Jerusalem at the centre of the labyrinth, not the devil.

This alternative, positive meaning ties in with the goat / lamb doubling /

superimposition.