My novel The Angels of L19 is a work of Christian fantasy, according to the definition of Colin Manlove:

What we are concerned with are works [of fiction] which give substantial and unambiguous place to other worlds, angels, devils, Christ figures, miraculous or supernatural events (biblical or otherwise), objects of numinous power, and mystical relationship with some approximation of the deity; and all under the aegis of Christian belief.

This doesn’t mean that the book has any evangelical purpose. I’m not even a practising Christian, although I grew up in that world. But it does mean that the book takes Christian belief and the Christian supernatural seriously in the conviction that an engagement with Christianity is an engagement with moral and existential questions that should be of interest to anyone.

I wrote this novel for a doctorate in creative writing, and one of my arguments in my thesis is that Christian fantasy cannot be entirely orthodox in its theology. For it to work as fantasy, it must trespass beyond the bounds of orthodoxy: not necessarily by contradicting received belief, but certainly by supposing things of which canonical texts are silent (which it does not, of course, present as true). All the great historical examples of the genre do this: The Divine Comedy, Dr Faustus, Paradise Lost – even C. S. Lewis’s science-fiction trilogy.

Conversely, Christian fantasy that is committed above all else to advancing particular theological speculations as true not only commits a category error, but is usually shallow and kitsch as fiction: betraying the profundity of the truths it ostensibly tries to communicate.

Here I’d like to offer some possible comparisons to the way my book approaches the question of Christian belief. If you think the examples that follow have something to offer the Christian (or non-Christian) reader or viewer, you may find something of value in my book as well. If you think these examples are impious or blasphemous, chances are you won’t like what I’m doing either.

Not all of these examples concern the fantastic or the Christian supernatural (and the last on the list is not even literature/fiction), but they're all useful comparisons for the way I've approached questions of faith in my novel.

Charles Williams: I shall discuss Williams in more detail in a dedicated post, since he’s an important precedent for me, and my treatment of the supernatural is directly inspired by his novels. I’ll only note here that he’s been adopted by evangelicals (and others) as a respectable author largely because of his membership of the Inklings, the Oxford group in which Tolkien and C. S. Lewis were also members. His work was admired by Lewis in particular. But his actual beliefs and practice as a Christian, and the ways in which these were translated into his fiction, were rather stranger than that association implies. In particular, his interest in magic and ritual place him in a tradition going back to people like John Dee, and other Renaissance philosophers who saw no contradiction between Christianity and magic. Anyway, more on Williams later and elsewhere.

Flannery O’Connor: O’Connor is also a respectable Christian writer, in the sense that assessing her in these terms is relatively uncontroversial, perhaps in large part because she wrote about herself as such eloquently and persuasively. But if one were to read her fiction without knowing this, one might conclude that her intent was to parody and mock Christian belief. Consider ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’ in which the climactic revelation of divine grace appears to come at the murdering hands of a serial killer. Or 'The River', in which a character seeking the purification of baptism drowns. I haven’t read her novels, but the plot summaries similarly seem to lend themselves to skeptical interpretations. But then, how should grace manifest itself, if not through and beyond the manifold ways we attempt to debase and complicate its operations? This is, it seems to me, the central question O’Connor is trying to address. Like her, I am interested in this question – because I too am in need of grace. Which of us is not?

16 Horsepower: the songs of David Eugene Edwards, writing for the band 16 Horsepower, seem to be sung from the point of view of a series of Flannery O’Connor characters. The initial temptation might be to assume some Nick Cave–like theatricality, but this documentary reveals something quite different. In it, Edwards talks about how the music of Joy Division and other post-punk bands felt to him like just as important a way to approach and apprehend the divine as the gospel traditions he grew up with. There is an important truth here: the divine is a terrible thing (in the original sense of that word also familiar to Williams and O’Connor). It has nothing to do with piety, still less with sentimentality.

The Exorcist: I like both the book and the film, although the latter is probably the stronger, more original work. For a work denounced by many as evil, The Exorcist is likely to strike first-time viewers as surprisingly conservative. Indeed, it is quite plausible to read it as a piece of celebratory propaganda on behalf of the Jesuit order – apart, perhaps, from its troubling ending, in which Father Karras, left alone after the more experienced Father Merrick has succumbed to a heart attack, and frustrated by his apparent failure to drive out the demon Pazuzu, invites it to leave Regan and enter him, and then commits suicide to prevent it taking him over. Needless to say, this conclusion is not consistent with the beliefs and practices of contemporary exorcists, researched by Blatty before writing the book. For them, the power of Christ is more than sufficient to defeat any demon – without any misguided and arrogant assumption of personal responsibility. But this plot development is a pretty clear demonstration of how the demands of approved theology and the demands of fictional dramatization might clash: Karras’s actions make perfect sense in dramatic terms. Troubled by doubts throughout the story, this is his final declaration of faith, in which he imitates Christ by sacrificing himself. Whether one is willing to accept this as a legitimate idea for the novel and film to propose depends on accepting that fiction and theology have different purposes.

The Last Temptation of Christ: I only know the Scorsese film, not the source novel. This was of course the target of a sustained campaign of protest denouncing it as blasphemous upon its original release. The most frequently cited source of complaint was the climactic sequence in which Christ, on the cross, imagines a different fate for himself, in which he might have married Mary Magdalene and lived out a ‘normal’ life as a husband and father. This is the titular ‘Last Temptation’. But underlying this is the more troubling idea that, in the film, Jesus is not initially sure that he is the Son of God. Perhaps his call to take up this mantle is actually an act of outrageous presumption? Both these elements have no canonical justification in the Gospel texts. But they seem to me to be perfectly legitimate as fiction: as attempts to think through the meaning of incarnation. How exactly does God become man? Of course He must lay aside omnipotence. Is it really so outrageous to suppose that He lays aside omniscience as well? That just as He must struggle to overcome sin, He might also struggle to overcome doubt? There is nothing blasphemous in this. Unless fiction about God is in itself somehow blasphemous.

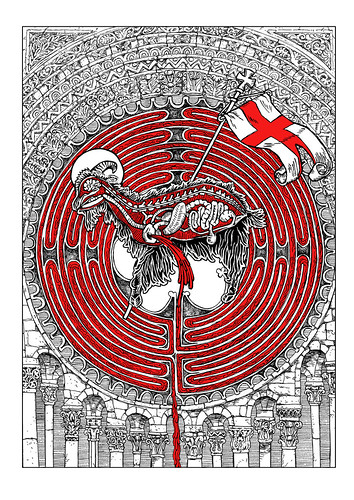

Piss Christ by Andres Serrano: this is a work of art of quite astonishing notoriety. Over thirty years after its creation, it is still being cited with outrage as an example of everything that is wrong with modern art, and a reason why artists should not receive public funding. It is a sculpture – although it is generally represented and reproduced via a series of photographs taken by the artist, and I'm not sure it still exists in any other form – in which a cheap plastic crucifix is depicted immersed in urine. My thoughts on this are influenced by a Twitter thread, which I can’t find now, but which I paraphrase to some extent in what follows. This work, like The Last Temptation of Christ, is about incarnation. Obviously I’ve never given birth: nor have I even been present at a birth. But I do know it is a pretty messy and excruciating event, involving a lot of bodily substances beyond the rather neutral and untroublingly transparent amniotic fluid. And Christ, moreover, was born in a stable: not places typically known for their perfect cleanliness and freedom from bodily excreta. And when Christ died on the cross, do you think that didn’t involve involuntary body functions either? God chose to become man: to subject Himself to all this: to immerse Himself in all this. To insist that it did not compromise his godhood to be vulnerable in this way. A cheap plastic crucifix presents Christ’s body as smooth and integral, as sentimental and kitsch: not as violated and broken for us. Serrano’s work is about all this: about our bad faith in sanitising what incarnation means. But if you insist on seeing Piss Christ as blasphemous, I suspect you’ll read the climax of my novel in the same way.

In that climax, I use a similar gambit to think about the relationship between abjection and transcendence: about abjection as a doorway to transcendence and the divine. In this I also follow O’Connor, and the medieval saints who kissed the sores of lepers as a way to approach God. And I follow Dante, for whom the way to heaven led through hell: down, down, all the way to the very bottom before beginning the painful ascent back up Mount Purgatory.