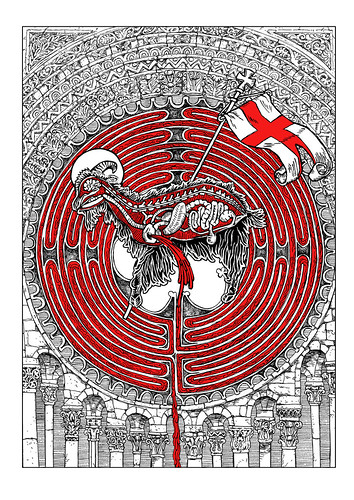

Here is a second illustration by Dan Hallett for my novel Brethren. Below is the script I initially sent to him:

Script for Dan

The second illustration is based on the iconography of the ‘Harrowing of Hell’. This legendary event purports to explain what Christ did between his death and resurrection: he went down into hell, to release the Old Testament patriarchs from limbo, and possibly preach to and rescue other ‘spirits in prison’. It was a popular story in the Middle Ages, via a compilation called The Golden Legend, and / or Latin translations of the original source, the so-called Gospel of Nicodemus (a late-classical fake).

Are you on Pinterest? There are some useful collections of medieval and early-modern visual representations there, e.g.: https://uk.pinterest.com/revjoelle/harrowing-of-hell/?lp=true

There are two basic ways of representing hell in these images: as a devouring mouth, or (seemingly much less common) as a walled city. In the former style, the mouth gapes open, and Christ seems to reach inside and lead people out by the hand. In the latter, he ‘besieges’ the gates of hell, and breaks them down, perhaps by striking them with his staff / ensign (which has the same St George’s Cross as the Agnus Dei).

In the Gospel of Nicodemus, there’s some suggestion Satan lets Christ into hell willingly, thinking Christ is defeated, not realising he’s bringing in a Trojan horse. In ch. 14 of Brethren, Jenny suggests that hell swallows Christ, but then vomits him out, because it can’t keep him down. I can’t find any visual suggestion of this last idea—perhaps because it’s too irreverent—but it echoes the story of Jonah and the whale, which was interpreted as an allegory of Christ’s death, i.e. Jonah in the belly of the whale is Christ in hell.

In keeping with the emphasis on the body in Brethren, we’re going to show hell as a mouth rather than a city. The mouth / face should have horns, and should vaguely (but not explicitly) suggest the head of a weird, demonic bull (because in the book hell is also depicted as the Minotaur / the bull-headed god Moloch). The pic will show a Robert / Everyman figure kneeling inside the mouth, hands clasped in prayer. But he’s not kneeling directly on the red tongue. Instead, he’s on a round, white communion wafer, which sits on top of the tongue. Hell is either about to try to swallow this wafer, or is in the process of vomiting it back out, but in any case, it’s sticking its tongue out, as if at the doctors.

Communion wafers are sometimes embossed with Christian symbols, one of which is the Agnus Dei (the image is also invoked in the words of the mass at the consecration of the host). Our wafer will instead by inscribed with the pattern / shape of the Chartres labyrinth from the first illustration, with Robert positioned at the centre. Not sure what this necessitates regarding the relative scale of Robert / wafer / hellmouth, but see if you can figure it out.

Re: the labyrinth pattern on the wafer. Don’t attempt to draw the path with two separate ‘sides’ enclosing a central space, as in the first illustration. Just do it as a single red line, to make it easier to draw at a smaller scale.

People in hell are always naked, so the only period indicators in medieval illustrations are in the general artistic style for human physiology (medieval faces often look a bit gormless to me)—and haircuts! But since this is (sort of) Robert, who at this point in the story has been hacking his own hair off with a pair of scissors for the past several years, his hair won’t be noticeably 80s in style. He’s also described as wearing dirty jeans in the final couple of chapters, so give him those too, but he’s bare-chested and barefoot. Robert’s ears are described as sticking out like Prince Charles in an early chapter, so give a suggestion of this, but don’t emphasise it too much, because we want to keep the dual significance whereby he stands for Everyman as well as himself (he should seem like a type rather than an individual). He should nonetheless look very much the worse for wear: bony and thin, but also a bit misshapen. He’s approx. 27 years old.

Christ stands outside the hellmouth. He’s carrying an ensign with the same design as the one in the scapegoat picture, and he has a halo. He is wearing a cloak with a shoulder brooch, as he is often represented. However, his body and face appear as that of a skeleton, like those which feature in a Dance of Death. It shouldn’t be a clean skeleton either, but one with tufts of hair, and gobbets of dried flesh and skin. Like these late-15th century examples: https://remedianetwork.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/dance-of-death.png

Skeletons in the Dance of Death sometimes have a jaunty or irreverent or mocking air. We don’t want that. This Christ skeleton should be serene and authoritative. It should also be drawn at a larger scale to Everyman / Robert, and it’s reaching down to offer its free hand for Robert to take.

Around the wafer, the hellmouth is vomiting up a flood of red wine (the blood of Christ, to accompany the body of the host). Perhaps the wafer is even floating on the flood, being carried forward out of the mouth, so the wafer’s like a raft for Robert—if you can make that work.

N. B. No demons in this hell: only the mouth.

I initially thought of having the hellmouth spewing its guts up, so that they flow around Robert and the wafer, and the coils of the guts would suggest (but obviously not directly reproduce) the shapes of the labyrinth, which in the text of Brethren is implicitly compared to both the inside of an ear and the packed cavity of the intestines. In the pic, Robert would then also be at the centre of this alternative labyrinth of guts. I don’t think this will work—it may not be obvious what the spilling guts are, or why they’re there, plus it will make the picture too busy. It’s better to keep the focus on the wafer and wine (the body of Christ inside the body of hell), but I mention it so you’re aware of some of the broader thematic issues, i.e. the association between hell and the (disintegrating, putrefying, turned inside-out) body.

Postscript

Dan did not draw Christ outside the hellmouth, reaching in to draw Robert / Everyman out. Instead, the dead Christ is inside hell, with His foot on the wafer that represents His resurrected body, which is on its way out of hell. This actually works better thematically.

Looking at the finished illustration, I thought it would not be obvious to the viewer that Robert / Everyman is kneeling on a giant communion wafer, so I added the following clarification to the end of the written text of the novel (the first illustration with the bisected goat is currently placed as a frontispiece, and this one as an endpiece):

Bill Forester once said: we remember a dead Christ, but our communion is with the risen Christ. Robert imagines a communion-wafer boat bobbing out of hell on a tide of wine. Because hell swallowed the dead Christ, but vomited up the risen Christ.

Then Christ swallowed hell.